Oil refineries and gasification of coal, biomass, and organic waste [1] are, in the last years, major producers of carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) emissions with related greenhouse effect, that lead to environmental concerns [2]. The stringent H2S environmental thresholds have triggered renewed interest in the modelling of sulfur chemistry [3]. Hydrogen sulfide is a very common and toxic by-product in fossil/bio-refineries, gas fields, geothermal and petrochemical processes, in fact, it is a well-known poison for industrial catalysts and its combustion products are responsible for acid rains. Nonetheless, H2S is a molecule very rich in hydrogen content, the richest one after methane, hydrocarbons, and ammonia.

Assuming this, H2S is not only a contaminant that as to be oxidized and converted into not harmful products (i.e. Claus process), but a new hydrogen source to be tapped in order to produce more modern and appealing products to self-sustain from economic and environmental viewpoint the whole process.

Carbon dioxide is responsible for a great impact on the environmental system [4] without relevant industrial uses due to its thermodynamic stability and low chemical value. The environmental concerns relating to CO2 as a greenhouse gas pushed toward a challenging carbon dioxide sequestration by different processes: chemical-physical washing and consequential disposal in remote storage [5]. Nowadays, the carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology has been studied by various researchers [6]. The process covers a broad range of technologies that are being developed to allow carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel using at large point sources in order to be transported to safe geological storage, rather than being emitted to the atmosphere [7].

In the last decade, scientific and technical efforts were made to mitigate the CO2 impact and other contaminants (i.e. hydrogen sulfide) by reducing its net production with renewable energies. Despite this, nowadays CO2 is used as a feedstock in only two large-scale industrial processes, such as methanoland urea [8] synthesis that are able to mitigate only 1% of carbon dioxide emissions, despite the high capacity of those plants. Some promising processes, for recycling CO2, are also Fisher-Tropsch synthesis [9] and catalytic CO2 but they still are in a demonstrative scale or they are high energy-consuming [10].

The sulfur removal technologies are found, instead, in very different stages of innovation, some are deeply studied as the thermal decomposition [11]; others are found in the pilot stage or at the threshold of demonstration [12][13]. Some others are in a very early stage of technical development or in the conceptualization stage for example [14] have studied a non-thermal plasma reaction, in which the cold plasma conditions and the adoption of dedicated catalysts can achieve high H2S conversion but the residence time appears significantly long.

Most of the recent studies are focused on carbon dioxide capture and sulfur recovery individually, so acid gas treatment researches are still limited. [15] has set a dynamic pilot plant to carry out CO2 capture from acid gas using the aqueous mono-ethanolamine (MEA) at various concentrations and temperatures and considered different thermodynamic models to calculate absorption and desorption of carbon dioxide in gas feed varying CO2 concentration in acid gas feed. [16]) proposed a modification for Claus process in order to increase sulfur recovery efficiency from acid gas, reduced the number of catalytic unit and hence, lowered the operating cost. Along with these new technologies, numerical and experimental examinations are still an interesting research topic. [17] have studied on acid gas removal for syngas, using a modified mechanism to simulate the pyrolysis of acid gas, with due accounting for pyrolysis and oxidation reactions. In 2016, a laboratory-scale reactor for producing syngas from acid gas had been used by [18] to provide information on different operating conditions.

Acid gases often contain other impurities that include nitrogen (N2), ammonia (NH3), carbon disulfide (CS2), carbonyl sulfide (COS), and hydrocarbons such as benzene (C6H6), toluene (C7H8), and xylene (C8H10) (BTX). At industrial level the standard Claus process is commonly used for the treatment of acid gas to recover elemental sulfur [19]. However, the efficiency of this process is significantly hindered by the presence of impurities and compositional variations of acid gas in the feed stream to Claus plant; in particular, the high content of CO2 in acid gases poses several environmental and technical issues in the operation of Claus plants [20].

The proposed technology (AG2S™ – Acid Gas to Syngas) exploits the amount of CO2 without any use of hydrogen or costly reducing agents; in fact, another emission, H2S, CO2 without any use of hydrogen or costly reducing agents; in fact, another emission, H2S, is coupling with it for producing syngas and consequently other valuable chemicals (ammonia and liquid fuels)[21][22]. According to the overall reaction:

2H2S + CO2 → H2+CO+ S2+ H2O (1)

The reaction is possible when both the molecules are in co-presence, so this technology allows to use energy sources currently unexploited such as crude oils, natural gases, geothermal sources, and different coals [23]. It is important to point out that such a reaction is chemically nobler than the traditional Claus reaction, as the hydrogen in H2S is not nailed in water, but it is freed to form hydrogen. This is an attractive alternative, also because the large volume of CO2 in lean acid gas can be captured from the produced syngas and recycled back to produce other syngas.

The presence of impurities, such as hydrocarbons in acid gas will also be an added value since this will favour a higher yield of syngas. Moreover, hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO) produced, can then, be used in industry for energy and power generation, in fact, syngas is a valuable commodity fuel in gas engines too. All these considerations have pushed research and development for captive use of H2S and CO2 to improve the accounting of these by-products [24].

The aim of this work is to demonstrate the sustainability and feasibility of the technology, applied to real industrial cases and comparing it with the Claus process considering some critical parameters (H2S and CO2 conversion, reaction temperature, recombination effects and carbon dioxide reuse). To test its potential at industrial level, a techno-economic estimation involves both the CAPEX and OPEX aspects was carried out to take in account an industrial data of SRU plants and building a greenfield case for the new technology. Exploiting extensive scientific works and experimental and operating experience, the new route process looks to be very promising.

In this section, process descriptions, initial conditions and computational tools were given. DSMOKE® software was used for simulating Claus process and AG2STM technology.

In the furnace, the temperature range is between 1223 and 1573 K and the pressure varies from 1.01 to 1.51 bar, along with the waste heat boiler is simulated at 640 K It is well known that acid gases contain a considerable amount of CO2. In order to estimate the reuse of CO2, the models were also run with different percentages of CO2 inlet compositions varying from 25% to 44% at 1373 K and 640 K in the thermal furnace and WHB respectively. The innovative reaction can be used when streams with both CO2 and H2S are presented. Temperature and pressure ranges were chosen according to the average operation temperatures reported in the literature.

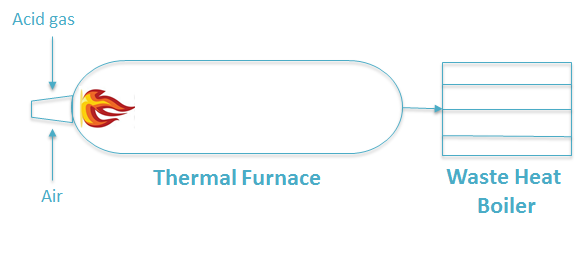

In a typical Claus process, the thermal part consists of a burner, a thermal furnace (TR) and a waste heat boiler (WHB). In this study, the burner and thermal furnace were modelled as one plug flow reactor, and the waste heat boiler was simulated as a bundle of several PFRs as shown in Figure 1.

Thermal section of a typical Claus process

The horizontal furnace reactor was modelled by assuming:

•Steady-state operation condition;

•Adiabatic condition (well-isolated furnace);

•Ideal gas mixture (due to high temperature and low pressure);

•Fully developed flow both in TR and WHB;

•Absence of fouling;

•Inlet streams are acid gas and air. Air can be enriched by oxygen supply.

In this work, the air was not enriched and was carried with 21% of oxygen. Table 1 shows the properties of inlet streams of sulfur recovery unit (SRU) obtained from industrial plants and used also for simulating the novel technology, suitably separating the main flow from the impurities.

Inlet operating conditions and geometry parameter

|

Acid gas |

Air |

|||||||

|

Flowrate (kg/h) Temperature (K) Pressure (bar) Composition (% molar) |

4230 398 1.59 |

8907 318 1.59 |

||||||

|

H2S CH4 N2 O2 C2H6 C3H8 H2O CO CO2 H2 NH3 |

0.7955 0.021 0.000 0.000 0.014 0.019 0.064 0.003 0.066 0.004 0.005 |

0.000 0.000 0.714 0.189 0.000 0.000 0.097 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 |

||||||

|

TR length (m) TR internal Ø (m) WHB length (m) WHB internal Ø (m) WHB tube number (-) |

6.500 1.550 6.000 0.050 470 |

|||||||

The oxidation reactions take place in the flame zone that is 0.1 - 0.5 m of the furnace. The other reactions occur along the thermal section of the reactor.

At high operating temperatures, S2 is the dominant allotrope of the elemental sulfur. Therefore, in this work, elemental sulfur was mentioned as S2, even if, it has allotropes such as S1 to S8.

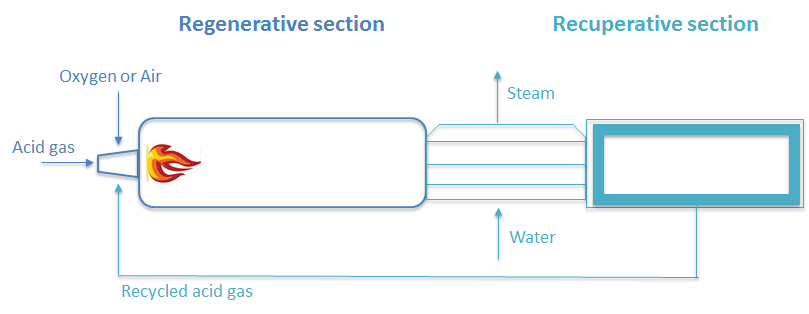

The thermal section of AG2STM process is made by regenerative thermal reactor (RTR), which has a different configuration compared with Claus process. It has a thermal reactor, waste heat boiler and a heat exchanger. The main point is to feed the preheated acid gas with an optimal H2S/CO2 ratio. Therefore, the demanding oxygen or air stream is much lower than the one required in Claus process. Thermal reactor and WHB were simulated considering them as an adiabatic and a non-isothermal PFRs, respectively.

AG2STM process scheme

AG2STM process was studied using the Simulation Suite PRO/II® by Schneider-Electric Simulation Science, using SRK (Soave-Redlich-Kwong) equation of state as thermodynamic model. The process scheme of the AG2STM is shown in Figure 2 . In order to use this technology at industrial level, it is necessary to revamp existing Claus plants, modifying some of the current used unit operations, in particular the thermal furnace and keeping unchanged the catalytic section. The design of the new reactor has allowed the overcoming of the problem: the implemented solution consists in a thermal regenerative reactor (RTR). In this configuration the efficiency of the process is improving by burning a proper amount of H2S in order to minimize generation of steam and obtained an autothermal reactor.

Fresh reactants (CO2 and H2S coming from upstream plants, assisted by air or oxygen) are injected along with recycled reactants into RTR. The recycle can be also mixed with fresh reactants before pre-heating and injection into the reactor recycle for improving self-sustainability of the plant from process standpoint, that is, for reduction or elimination of exhausts.

For assuring a proper production yield, it is essential to prevent any possible recombination effects, which have been proven to be significant during relatively slow cooling; for this purpose, a Waste Heat Boiler (WHB) is installed just at outlet of RTR to quench the reactions.

The WHB and recycle pre-heating equipment play a key role in the regenerative process,

therefore, they could be considered a portion of the RTR. On the whole, the RTR could be also seen as a system constituted of a “regenerative” and a “recuperative” section, and not just the reaction chamber itself.

As mention the aim of this process is to recover as much as possible hydrogen from the H2S molecule, in order to be able to produce a huge amount of syngas. In order to allow the pyrolysis of H2S high temperatures (1273 - 1473 K) [25] are necessary to: (i) activate the reactive system from chemical-thermodynamics standpoint, (ii) quicken kinetics and (iii) reduce by-products.

The outflow of the catalytic reactor, which includes a certain amount of syngas, must be purified from the unreacted acid gas (H2S and CO2). The simulation of the catalytic reactor is carried out using conversion reactor in Pro/II. Al2O3 sites hydrolyse COS and CS2 and support the dispersed elements that allows to increase the conversion up to 70% in the new technology and it is about 99% for Claus reaction [26].

The AG2STM technology approach at real plant results to be a novelty, both processes were simulated with several field data using DSMOKE. The software is a general framework developed by our research group for numerical simulations of reacting systems with detailed kinetic mechanisms including thousands of chemical species and reactions [19], involving radicals and complex mechanism to explain all the main reactions of the process.

For each reactor, 146 species mass balances, one global mass balance and one energy balance were solved, using standard material (eq. (2)) and energy balances (eq. (3)) of plug flow reactor:

(2)

(3)

In this section, simulation, recombination effects, carbon dioxide effect of refineries and Greenfield economic assessment results were given.

The evaluation of the potential application of AG2STM technology on sulfur recovery is related to the quantity of H2S presents in the feedstock. In this work to prove the validity of the process a feedstock containing 23% of H2S was chosen. The feed composition is reported in Table 1. Because Claus process operates at quite high temperatures, the temperature range was chosen as 1223 - 1573 K in this work.

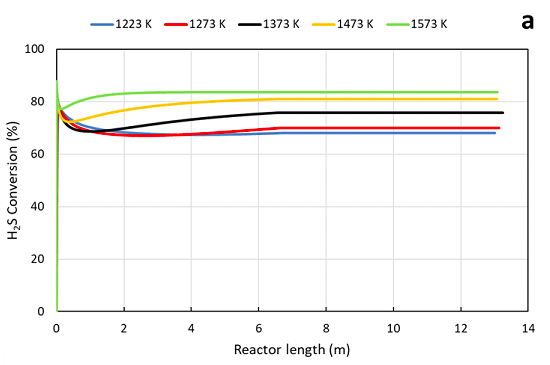

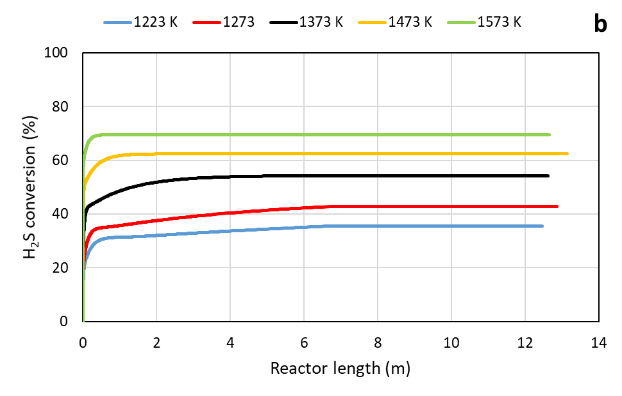

According to the simulation results, Figure 3 shows the dependence of H2S conversion, of both processes, in function of the temperature. The conversion of H2S is increasing gradually with an increase of temperature and achieving 70% and 83% for AG2STM and Claus processes, respectively.

The acid gas and air meet in the burner, which is the first step of the Claus furnace. In that part, hydrogen sulfide conversion increases fast depends on the oxidation reactions, in fact the conversion at all temperatures are in a range of 70 - 83%.

Instead, in AG2STM technology the feed is preheated in order to achieve the maximum hydrogen sulfide conversion. The reaction between H2S and CO2 (Equation 4) occurs immediately due to high activation energy. The hydrogen sulfide conversion achieve minimum ≈ 30% at 1223 K and maximum ≈ 70% at 1573 K . These results show that the conversion is strongly dependent of operating temperature.

Conversion of H2S in Claus (a) and AG2STM (b) in function of temperature (K)

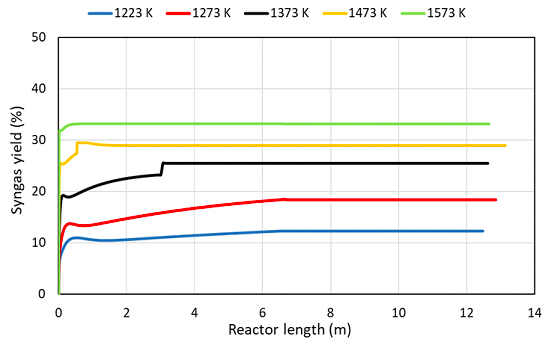

Together with decreasing H2S content, one of the main purposes of AG2STM process is to quantify the production of syngas. It is a valuable commodity for use as a fuel in gas engines or to produce valuable chemicals such as ammonia and liquid fuels.

Yield of syngas is an important indicator of process feasibility. It is defined as ratio between moles of syngas and moles of reagents:

(4)

where xi is the molar fraction, F is the molar flow rate and Fo the initial conditions.

The yield of syngas producing respect to initial reagents is shown in Figure 4. Hydrogen and syngas production have been widely studied. According to [27], the temperature is the most influent factor for pyrolysis, and increasing the temperature, resulted in increase in gas yield and more hydrogen production. The optimization of temperature is around 1473 K for the process. The results illustrated that higher temperature was needed in the process up than 1373 K to maximize syngas yield.

The low temperatures are not be able to activate the reactive system from chemical-thermodynamics standpoint; hence, at the temperatures lower than 1373 K, the syngas yield is very low and the time which is needed for the occurrence of main reactions is longer. Besides, the side reactions completely occur along with the main reactions at 2.5 m, 0.4 m, and 0.25 m at the temperatures 1373 K, 1473 K, and 1573 K, respectively. The peaks show that the reactions take place quicker and the yield rises by increasing the temperature, as expected.

Syngas yield AG2STM technology in function of operating temperature (K) and reactor length

Table 2 shows the molar fraction of CO2 in function of operating temperature. As seen in table CO2 conversions, obtained from Claus furnace are almost equal at any considered temperature. Instead, the new technology is strongly dependent on the temperature and achieves the best CO2 conversion up than 1473 K.

CO2 molar fraction in thermal reactor and waste heat boiler outlets

|

AG 2 S TM technology |

Claus process |

|||

|

Temperature (K) |

TR outlet |

WHB outlet |

TR outlet |

WHB outlet |

|

1223 1273 1373 1473 1573 |

0.1706 0.1358 0.0914 0.0741 0.0607 |

0.1709 0.1368 0.0915 0.0743 0. 0611 |

0.0409 0.0426 0.0447 0.0397 0.0329 |

0.0425 0.0439 0.0455 0.0402 0.0336 |

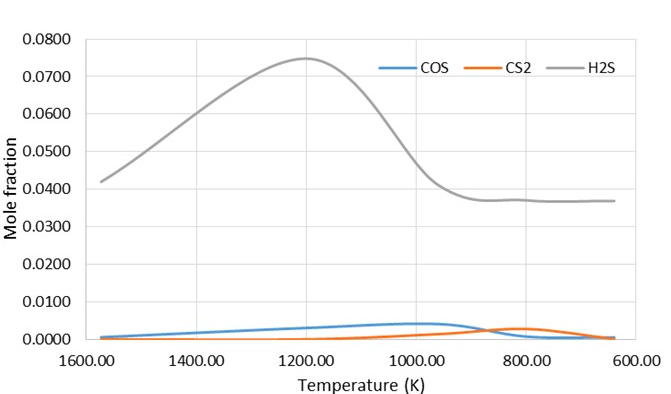

The hydrogen sulfide decomposition reaction plays an important role in the formation of CO and COS. In fact, the recombination reactions (eqs. (5)-(7)) that occur at the front of the WHB are:

H2 + ½ S2 ⇌ H2 S (5)

CO + ½ S2 ⇌ COS (6)

CH4 + 2S2 → CS2 + 2H2S (7)

These reactions not only influence sulfur recovery, air demand, and hydrogen production in the SRU, but they also affect the performance of the WHB.

The COS and CS2 are formed in the front-end units, i.e. the TR and the WHB. They can be converted to H2S and CO via hydrolysis reactions in the catalytic converters. The main reaction occurring in the converters is favoured thermodynamically at lower temperatures (623 K). At these temperatures the hydrolysis reactions are kinetically limited which often results in little conversions of COS and CS2. The unconverted COS/CS2 fend up in the tail gas where they represent a large proportion of the sulfur content. The temperature profile’s trend shows a great stability of the COS species at high temperature (1273 - 1573 K) while it is possible to note an inverse trend for the CS2 species which is more stable at low temperature. The formation of these species is mainly due to the presence, albeit in small quantities, of H2S in the WHB unit in which the reactions eq. (6) and eq. (7) take place.

Recombination products concentrations of WHB in function of temperature

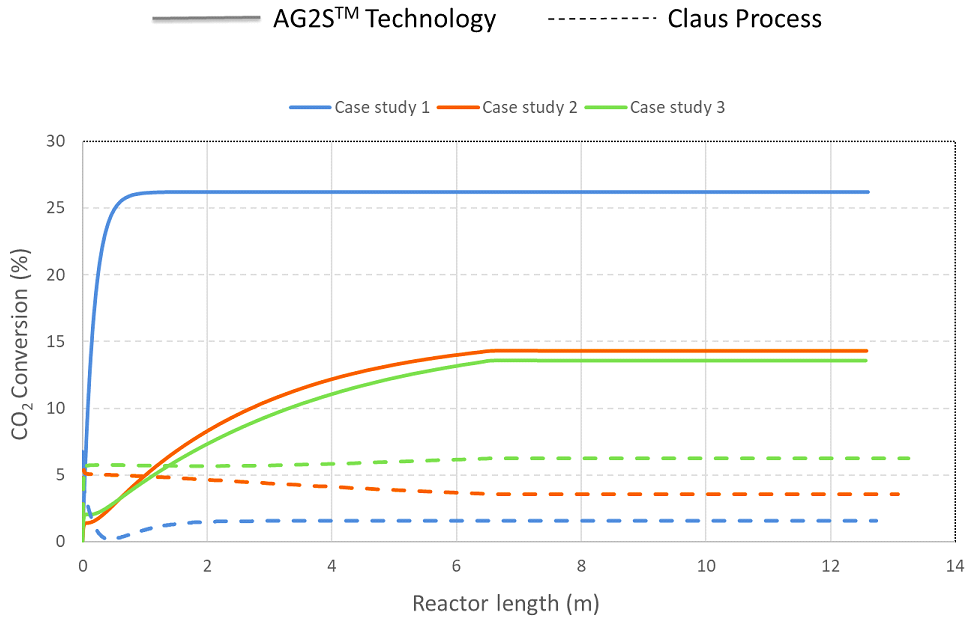

The investigation of CO2 effect was done by taking into account three feed based on different CO2 content, because it is well-known that AG2STM achieves its better performance with high CO2 content. The data of two Oil Refinery Companies located in Mesaieed, Qatar and one in Nanjing, China are used as references. They were mentioned in this study as case study 1, 2 and 3 which contain 25 mol %, 39 mol % and 44 mol % of carbon dioxide respectively.

As seen in Figure 6, CO2 effect are strongly influence of feed composition, this shows that efficiency of AG2STM process is strongly dependent on inlet CO2.

The results illustrate that the novel technology has a significant predominance comparing with Claus process in terms of CO2 conversion. Following the graph in Figure 6 (straight line), there is a linear dependence between the CO2 content and its conversion, in fact the process achieves 27% conversion when the molar composition is 44%. In the Claus process in Figure 6 (dotted line) the trend is the reverse and the conversion is low (1.5 - 6%), due to a not optimal figuration; in fact, reducing CO2 is not the main target of this process. However, the reactions occur in the furnace are not able to eliminate carbon dioxide sufficiently, a further step is required.

CO2 conversion in AG2STM technology (straight line) and Claus process (dotted line) in function of carbon dioxide inlet composition and reactor length

Previous data have demonstrated the functioning of AG2STM in a specific range of applicability. In this section the first basic economic evaluation is performed.

Chemical plants are, of course, built to create value, that is – in a medium-term – make profits; thus, the estimates of the investment required (CAPEX, Capital Expenditure) and of the annual Cash Flows (CF, embedding the Operational Expenditure, OPEX) are needed so that the profitability of any initiative can be assessed. The items to be estimated so as to sum up to the cash flow are the variable costs of production, the fixed costs of production (overall, OPEX) and the revenues from sales, including both main products and by-products considering green-field scenarios (Table 3).

In this section, the economic assessment was carried out referring to Chemical Engineering Design [28]. The cost of the plant was established for the CAPEX (which includes also Inside Battery Limits (ISBL), cost of the plants itself, Offsite Battery Limits (OSBL), cost of modification and improvements to be made to the site infrastructure, engineering and construction costs and, working capital and contingency charges); as for the revenues’ and costs’ estimation, the following parameters have been included: the prices of raw materials such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide; carbon dioxide taxation at 20%; utilities’ costs and exploited production capacity.

A study on greenfield case is made in order to have an early stage of the project design. The results show that there is an increase in the revenues greater than the one of investment costs. Even though a lot less impacting on the global level, aiming to reduce CO2 emissions which come from refineries, the development of the technology as an alternative to the Claus process needs to be considered.

In this section, the estimation of the CAPEX, the revenues and the variable and fixed costs of production are presented. In fact, in this case, the designed process section needs to be built from scratch, so the case needs to be managed as a project on its own. All costs related to the construction of a whole new plant are scaled on the single section and so a project profitability study can be carried [29].

Greenfield case fixed costs of production

|

Fixed costs |

UDS/a |

|

Operating Labor |

240 000 |

|

Supervision |

60 000 |

|

Direct Salary Overhead |

150 000 |

|

Maintenance |

112 500 |

|

Property and Insurance |

37 500 |

|

Rent of land |

52 500 |

|

Total |

652 500 |

The added expenditures to be considered are show in Table 4. These are fixed costs of production, which means independent of the fact that the plant is producing and from the production volumes themselves.

Considering that the plant needs to be started for the first time, the Working Capital contribution needs to be accounted for. It is assumed to be 5% of ISBL+OSBL and of course, it is added to the CAPEX since it is not an annual cost.

In this analysis, the cost of the furnace and waste heat boiler are taken in account and added to the previously estimated ISBL. The geometry of the thermal furnace, the waste heat boiler and catalytic bed is maintained unchanged.

For the catalyst characteristics, previous work of [30] has been followed, assimilating their catalyst features (bed density and volume of catalyst per volume of reactor) as the standard ones for the Claus process. All calculations made for the case study are reported in Table 4 together with details of CAPEX contributions.

Greenfield investment costs

|

Greenfield |

UDS |

|

ISBL OSBL ISBL+OSBL Contingency CAPEX Working Capital |

3 750 000 1 500 000 5 250 000 375 000 5 625 000 262 50 |

The total ISBL results to be 3 750 000 UDS with 1 - 150 000 USD to be accounted for depreciation. This cost appears to be very low and so the greenfield case very promising. All costs and revenues for the study are resumed in Table 5.

Cost and revenues for CO2 price equal to 20 $/ton

|

Revenues |

UDS/a |

|

|

Variable costs Fixed costs |

S2 H2 CO CO2 taxes Total Steam O2 Electricity Cooling water Total Total |

2 078 080 424 290 137 040 105 900 2 745 310 973 200 480 000 95 760 46 800 1 595 760 652 500 |

|

CAPEX |

Total |

5 890 000 UDS |

The CO2 abatement, the syngas production and the exploitation of this promising technology in a greenfield case were considered. The greenfield results allow to certainly state that investment was worth taking.

This work investigates an inventive solution for potential improvements of petrochemical/power plants performance: Acid Gas to Syngas™ technology. Such a synthesis route, from thermodynamics and kinetics studies, appears feasible and promising from technological standpoint. The development has been described using experimental and industrial data, together with an efficient numerical calculation, in order to carry out technical and economical evaluations of a possible feasibility and process utilization. A wider range of acid gas inlet compositions were investigated: in particular feed with higher carbon dioxide content provided by Nanjing (China) (44 mol %), or the Mesaieed (Qatar) (25 - 9 mol %) industrial plants in order to analyze the effectiveness of Acid Gas to Syngas™ (AG2S™). Results stated that the optimization of all the sensitive parameters (fast quench, low injection of oxygen, good ratio of reagents, inlet temperature) greatly improves the sustainability of the process in terms of quality of syngas produced, limiting, in the meantime the emissions. The economic analysis shows that Capex and Opex results of the greenfield case looks to be very promising for a pilot plant setup. Future analysis spectrum could lead to considering technological applications not only limited to the SRU of refineries; an example could be the direct methanol production or urea synthesis made with this new process route.

Authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) 2214/A Doctoral Research Grant Program.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

AG2STM |

Acid Gas to SyngasTM |

|

CAPEX |

Capital Expenditure |

|

CCS |

Carbon Capture and Storage |

|

ISBL |

Inside Battery Limits |

|

OSBL |

Offside Battery Limits |

|

RTR |

Regenerative Thermal Reactor |

|

SRU |

Sulfur Recovery Unit |

|

TR |

Thermal Reactor |

|

WHB |

Waste Heat Boiler |

- ,

Cleaner energy for cleaner production: Modelling, simulation, optimisation and waste management ,Journal of Cleaner Production , Vol. 111 ,pp 1-16 , 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.062 - ,

Energy E ffi ciency and Greenhouse Gas Emission Intensity of Petroleum Products at U . S . Re fi neries , 2020 - ,

A predictive kinetic model of sulfur release from coal ,Fuel , Vol. 91 (1),pp 213-223 , 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.08.017 - ,

Examining the impact factors of energy-related CO2 emissions using the STIRPAT model in Guangdong Province, China ,Applied Energy , Vol. 106 (2013),pp 65-71 , 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.01.036 - ,

Preparation and characterization of fuel pellets from woody biomass, agro-residues and their corresponding hydrochars ,Applied Energy , Vol. 113 ,pp 1315-1322 , 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.08.087 - ,

What's the most cost-effective policy of CO2 targeted reduction: An application of aggregated economic technological model with CCS? ,Applied Energy , Vol. 112 ,pp 866-875 , 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.01.047 - ,

A Techno-economic analysis and systematic review of carbon capture and storage (CCS) applied to the iron and steel, cement, oil refining and pulp and paper industries, as well as other high purity sources ,International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control , Vol. 61 ,pp 71-84 , 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2017.03.020 - ,

Worldwide innovations in the development of carbon capture technologies and the utilization of CO2 ,Energy and Environmental Science , Vol. 5 (6),pp 7281-7305 , 2012, https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ee03403d - ,

Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: EXAFS study of Ru and Pt bimetallic Co based catalysts ,Fuel , Vol. 132 ,pp 62-70 , 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.04.063 - , , CO2 as feedstock: A new pathway to syngas, 2015

- ,

CS2 formation in the claus reaction furnace: A kinetic study of methane-sulfur and methane-hydrogen sulfide reactions ,Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research , Vol. 43 (13),pp 3304-3313 , 2004, https://doi.org/10.1021/ie030515+ - ,

Hydrogen from hydrogen sulfide: towards a more sustainable hydrogen economy ,International Journal of Hydrogen Energy , Vol. 44 (3),pp 1299-1327 , 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.10.035 - ,

Metal sulfide-based process analysis for hydrogen generation from hydrogen sulfide conversion ,International Journal of Hydrogen Energy , Vol. 44 (39),pp 21336-21350 , 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.06.180 - ,

Highly selective conversion of H2S-CO2 to syngas by combination of non-thermal plasma and MoS2/Al2O3 ,Journal of CO2 Utilization , Vol. 37 (November 2019),pp 45-54 , 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2019.11.021 - ,

Experimental, simulation and thermodynamic modeling of an acid gas removal pilot plant for CO2 capturing by mono-ethanol amine solution ,Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering , Vol. 72 (June),pp 103001 , 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2019.103001 - ,

Dual-stage acid gas combustion to increase sulfur recovery and decrease the number of catalytic units in sulfur recovery units ,Applied Thermal Engineering , Vol. 156 (July 2018),pp 576-586 , 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.04.105 - ,

Numerical Examination of Acid Gas for Syngas and Sulfur Recovery ,Energy Procedia , Vol. 75 ,pp 3066-3070 , 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.628 - ,

Experimental examination of syngas recovery from acid gases ,Applied Energy , Vol. 164 ,pp 64-68 , 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.11.025 - , , Total plant integrated optimization of sulfur recovery and steam generation for Claus processes using detailed kinetic schemes, 2013

- ,

Modeling a claus process reaction furnace via a radical kinetic scheme ,Computer Aided Chemical Engineering , Vol. 18 (C),pp 463-468 , 2004, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1570-7946(04)80143-3 - ,

Acid Gas to Syngas (AG2S™) technology applied to solid fuel gasification: Cutting H2S and CO2 emissions by improving syngas production ,Applied Energy , Vol. 184 ,pp 1284-1291 , 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.06.040 - ,

SYNGAS PRODUCTION BY C02 REDUCTION PROCESS , (12),pp 2016 , 2015 - ,

Novel coal gasification process: Improvement of syngas yield and reduction of emissions ,Chemical Engineering Transactions , Vol. 43 (1),pp 1483-1488 , 2015, https://doi.org/10.3303/CET1543248 - ,

Hydrogenation of CO2 to value-added products - A review and potential future developments ,Journal of CO2 Utilization , Vol. 5 ,pp 66-81 , 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcou.2013.12.005 - ,

Mitigating carbon dioxide impact of industrial steam methane reformers by acid gas to syngas technology: Technical and environmental feasibility ,Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems , Vol. 8 (1),pp 71-87 , 2020, https://doi.org/10.13044/j.sdewes.d7.0258 - ,

Characterization of several kinds of coal and biomass for pyrolysis and gasification ,Fuel , Vol. 152 ,pp 138-145 , 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.09.054 - ,

Biomass gasification for hydrogen production ,International Journal of Hydrogen Energy , Vol. 36 (21),pp 14252-14260 , 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.05.105 - , , Chemical Engineering Design. Principles, practice and economics of plant and process design, 2013

- , , Chemical Process Equipment Design, 2017

- ,

Kinetic modelling of a commercial sulfur recovery unit based on Claus straight through process: Comparison with equilibrium model ,Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry , Vol. 30 ,pp 50-63 , 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2015.05.001